Exploring autism 1971-2021

The historical context

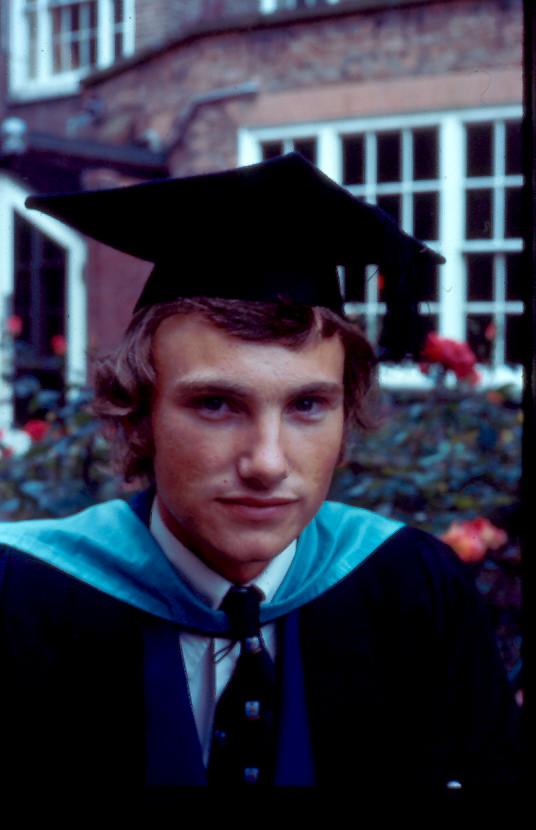

Tony Graduating from The University of Hull in July 1973

In 1971, I had completed my first year studying psychology in England. During the summer vacation I became a volunteer at a special school in my hometown of Birmingham. It was at this special school that I first encountered autism as expressed by two young children. Russel was 7 years old and Sarah five years old. They were both agile and alert, but mute and preferred to engage in solitary play. Neither used gestural communication to replace their lack of speech and both were extremely sensitive to specific noises. They were frequently distressed by changes to their daily routine and the social, sensory, cognitive and communication experiences in the classroom and playground. They seemed in a world of their own, and other children were not invited into that world. However, I was determined to make a connection and to see the world from their perspective. Gradually and carefully, I became accepted, as a temporary but welcome visitor to their world.

The experience was profound emotionally and intellectually, and I decided that my career as a psychologist would be to explore and understand autism. In the autumn of 1971, I returned to University determined to read all I could on autism. There were only around a hundred published journal articles on autism, and perhaps two or three academic books and biographies written by parents of autistic children. Within a few weeks I had read all the relevant literature published in the English language. There are now over 7,000 journal articles on autism published each year and a corpus of research papers of over 70,000 studies of autism. Today I cannot keep up with the explosion of scientific knowledge on autism and tend to read the papers on the aspects of autism that intrigue me, and the papers of my colleagues and leading authorities on autism.

Changing concept of autism

In the early 1970s autism was conceptualized as an expression of schizophrenia that was caused by defective parenting and treatment was psychoanalysis of the child and their mother. However, during the late 1970s research studies and clinicians began to change this conceptualization to be replaced by autism being perceived as a neurodevelopmental disorder with a distinct profile of social, cognitive, linguistic, and sensory abilities that can be apparent in early infancy. This is the autism ‘signature’ that we seek in a diagnostic assessment and the core structure of our formal diagnostic instruments such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule or ADOS. My extensive experience as a diagnostician has led to supplementing the formal diagnostic instruments with activities to examine aspects of autism such as Theory of Mind abilities, the concept of self, alexithymia and interoception, and adaptations to autism that affect the clinical presentation and prognosis.

In the early 1970s our conceptualization of autism was that it was a rare but conspicuous and severe disability. The trajectory was for the child to attend a special school and eventually to be admitted to an institution due to high support needs in daily living skills and challenging behaviour.

During the 1980s we started to explore the range of expressions of autism and prognosis that included children and adults who were severely and conspicuously autistic in early childhood, but who acquired the ability to talk and converse fluently, had intellectual abilities in the average and above average range, and attended a typical school. They appeared destined to become independent of their parents and achieve full time employment and perhaps a long-term relationship. They had progressed to an expression of autism that was more subtle with a quite different prognosis. Lorna Wing in London recognized the progression in abilities to a profile consistent with the descriptions of autism by Hans Asperger in Austria rather than Leo Kanner in the United States. She first used the eponymous term Asperger’s syndrome in 1981 and her colleague and my PhD supervisor, Uta Frith, translated into English his original description of autism, based on the children he saw at his clinic in Vienna. I became a member of a small group of psychologists and psychiatrists in London exploring a new dimension of autism, Asperger’s syndrome. We discovered that there were children with the profile of abilities described by Hans Asperger that had never shown signs of severe autism in early childhood. There were two pathways to Asperger’s syndrome.

The original prevalence of autism was based on the conceptualization of a severe disability and was estimated at around one in 2,500 children. When we included Asperger’s syndrome in the autism spectrum and recognized the wide range of expressions of autism, the current prevalence according to the Centers for Disease Control in the USA is estimated to be around one in 54 children. Autism is becoming increasingly recognized by clinicians, schools, employers, and the public. A recent development is to have an autistic character in television programmes and films and there are many popular autobiographies written by autistic adults such as Temple Grandin.

There have been changes in terminology and diagnostic criteria over the last 50 years, as we increase our understanding of autism. The term Asperger’s syndrome has been replaced in the 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders with the term Autism Spectrum Disorder Level 1. There are three levels of autism based on support needs. It is my opinion that we may change the terminology and diagnostic criteria, but the individuals remain the same in their daily challenges and abilities.

My recent research has included the design and development of screening instruments to identify the characteristics of autism in girls and women. The original gender ratio was 4 boys to each girl, but recent research indicates that the true ratio is 2:1. Girls and women can adapt to autism in ways that delay a diagnostic assessment.

Adaptations to autism

One of the central characteristics of autism, according to the DSM 5 diagnostic criteria, is a deficit in social communication and social interaction. The social and interpersonal aspects of life are a challenge to an autistic child or adult. So how does an autistic person adapt to these challenges? My extensive clinical experience suggests there are four potential adaptations based on personality and acquiring coping mechanisms: the introvert, the extrovert, the “camouflager”, and compensation.

The Introvert

The more easily recognized adaptation is that of the child who could be described as an introvert. The child, and subsequent the adult, actively minimizes or avoids social engagement, recognizing that social interactions are indecipherably complex, overwhelming, and stressful. This conspicuous adaptation, therefore, is to choose, where possible, to be alone to accomplish what you want to do without interruption, and not necessarily feeling lonely. The person’s energy is recharged in solitude, as being with people is at times bewildering and exhausting.

However, we are increasingly recognizing autistic children whose personality type is extrovert, being highly motivated to socialize. For these individuals, there are two potential adaptations that facilitate social engagement.

The Extrovert

The autistic extrovert actively seeks social engagement. Unfortunately, due to impaired ‘theory of mind,’ autistic children and adults have difficulties reading the subtle nonverbal communication used in a social interaction that regulate and moderate the fluency, reciprocity and intensity of social engagement. Unfortunately their social behavior may then be perceived as being intrusive, intense, or even irritating. A metaphor to describe this adaptation to autism is that of a driver who does not see the traffic signals (nonverbal communication) or abide by the traffic code (social conventions and context). They are unable to accurately read social situations and therefore criticized for behaving inappropriately.

While there is considerable motivation for social interaction and making friends, these experiences may nevertheless be ended prematurely by their peers. The consequence is that the autistic person feels bitterly disappointed that conversations, friendships, and relationships are short-lived, and social popularity remains elusive. When friendship is achieved, the autistic person can become possessive, idealizing their new friend with an intensity that is overwhelming. When the friendship or relationship ends, there can be intense despair and feelings of abandonment, betrayal, and of being misunderstood.

The Camouflager

The autistic “camouflager” is very aware of their difficulties in reading nonverbal communication and in making and keeping friends. With this insight, they are initially detached from their peers, but keenly observe their social interactions and the social behaviour of people in general. They seek to learn social ‘systems or rules and determine, interpret, and abide by those social rules. Their social abilities are achieved by intellectual analysis rather than intuition. Thus, effectively camouflaging their social difficulties. There is the creation of a social “mask.” We know that 70 per cent of ASD level 1 adults consistently use camouflaging in social situations. Research shows that autistic females tend to be better at camouflaging than males, and more likely to use this adaptation strategy in a wider range of social situations. However, some autistic males can use this adaptation.

The teenage autistic girl may have effectively camouflaged her autism, to “fly under the autism radar” and not have been considered for a diagnostic assessment with comments such as, “You’re too social to have autism.”. Every day at school (but probably not at home) she has acted the role of a typical schoolgirl, so much so that she should be awarded an Oscar for her social performance with her peers. She has a superficial sociability that is effective, but superficial and exhausting. She also has a lack of social identity, other than being the person that others expect her to be. Camouflaging can delay a diagnostic assessment for autism until the late teens or adult years which will also delay access to appropriate support and therapy.

There can be performance anxiety in social situations, as though she has been continually “on stage.” Like Cinderella at the ball, she can maintain the pretense for a while, but then becomes totally drained of mental energy and must return home to recover in solitude. She is likely to ruminate on her social performance in her bedroom and the high level of stress may evolve into an anxiety disorder or depression and self-harm.

The consequences of camouflaging autism can be a lack of knowledge of the inner and true self, with some adult women saying, “I don’t know who I am.” This may lead to a lack of self-identity, low self-esteem, and prolonged self-analysis. She recognizes that her friendships and relationships are based on deceit, where she has presented a “false” identity. This increases her feelings of deep inner loneliness. She yearns to find, and be able to be, her authentic self, but is aware that when her true self is revealed, she may be rejected and despised.

Psychotherapy needs to focus on the negative long-term consequences of camouflaging, encourage self-acceptance, and facilitate ways to explain the characteristics of autism to friends and colleagues so that others can accommodate and appreciate those characteristics to facilitate social acceptance and inclusion

Compensation

A fourth adaptation to autism is to create a lifestyle that minimizes the characteristics of autism. The autistic girl may prefer the company of boys, whose social dynamics are relatively simpler to decipher than girls. Boys may be more accommodating of someone who is socially clumsy, but who clearly enjoys and is relaxed in their company.

Compensation can also be achieved by developing an interest and talent in science, the arts and computer games, becoming an author, artist, musician, singer, multi-linguist, scientist and games designer. Social eccentricities are accepted and accommodated due to being valued by peers who recognize and admire a particular talent.

Another compensation strategy is to develop an interest in fictional heroes and superheroes and to have friendships based on shared interests, such as cosplay and Comic-Con, providing defined and recognized roles and achieving an alternative persona. The autistic girl may seek social assimilation by studying psychology and avidly reading books on body language and friendship or a career that does not involve much social engagement, such as becoming a wildlife ranger.

Other compensation strategies can include engaging in part-time schooling and employment to reduce the effects of exhaustion and having a social network of friends and colleagues who have autism—that is, people who accept and encourage the person’s autism. There is a much-valued sense of connection and authenticity.

Co-occurring conditions

We now recognise that there is an association between autism and anxiety, with approximately 80% of autistic children and adults feeling mildly anxious for much of their day, and for most of their life. They often experience intense anxiety in specific situations, such as when there are changes in routine or expectations, uncertainty in what to do or what is going to happen, fear of imperfection and making a mistake and specific sensory experiences. There can also be anxiety in crowded places such as a shopping mall on a Saturday. Research has confirmed that an anxiety disorder is the most common mental health problem for autistic adults. Sometimes, the level of anxiety experienced may be perceived as actually more disabling than the diagnostic characteristics of autism.

Research and clinical experience indicate that approximately one third of autistic adults experience cyclical feelings of sadness and pessimism that can evolve into a clinical depression. There are many reasons why an autistic person may become sad and depressed. These include feelings of social isolation, loneliness, and not being valued and understood by family members and colleagues. Another reason for depression is the exhaustion experienced due to socializing, trying to manage and often suppress emotions, especially anxiety, and coping with sensory sensitivity. The person is constantly alert, trying to endure perpetual anxiety whilst suffering a deficit in emotional resilience and confidence. The mental effort of intellectually analysing everyday interactions and experiences is draining, and mental energy depletion leads to thoughts and feelings of despair.

Recent research has explored the association between autism and alexithymia, that is the ability to recognize or describe one’s own thoughts and emotions. An autistic person will have genuine difficulty converting their thoughts and feelings into speech. When asked why they may have done something, or to describe their feelings regarding an event, they may simply reply, ‘I don’t know’. This is not their being obtuse or evasive, but an expression of a recognized difficulty with self-reflection and self-disclosure of inner thoughts and feelings through speech. Psychological therapy for mental health issues will need to accommodate the profile of abilities and experiences associated with autism, such as alexithymia, the lifetime experience of extensive bullying and teasing, and sensory sensitivity. We now have psychological therapy manuals specifically designed for adults who have autism and I have been able to contribute with my colleague Dr Michelle Garnett to many of the manuals and therapy programmes. We have designed and evaluated individual and group programmes for anxiety and depression, to build resilience to bullying and teasing, and acquire abilities in the areas from love and romance to employment.

There is increasing evidence that autism is associated with specific learning disorders such as dyslexia and hyperlexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, and specific language disorders. Thus, the diagnostic journey does not end with confirmation of autism. Conversely, the diagnostic journey for autism may start with the accurate diagnosis of another mental or personality disorder and a detailed developmental history indicates the presence of autism. Research and my own clinical experience suggest that around one in four patients with an eating disorder, substance abuse, gender dysphoria and borderline personality disorder have a dual diagnosis. There is also an association between autism and Tourette’s disorder, sleep disorders and bipolar disorders. Clinicians in all areas of psychology and psychiatry need to be aware of the characteristics of autism in a patient’s developmental history and profile of abilities. When the diagnosis is confirmed, adapt their psychotherapy to accommodate the autistic patient who has a different way of perceiving, thinking, learning, and relating compared to other patients.

While we acknowledge the concept of autism plus, we also acknowledge the concept of autism pure. Around 15 per cent of autistic adults have no additional diagnoses and they often have a different prognosis.

Long-term outcomes

Over 50 years I have been able to maintain contact with autistic children through to their mature years and see retired individuals for a diagnostic assessment. Those who have achieved a diagnosis of autism late in life are often greatly relieved to know why they are different and can now perceive their life through the lens of autism. The diagnosis can help explain why they were bullied and teased at school, their difficulties in making friends and maintaining a long-term relationship and sensory sensitivity.

The majority have described an improvement in their mental health after the age of 50, not necessarily by treatment from health professionals and medication, but discovering strategies themselves through reading, the Internet and experimentation. We are also now exploring the concept of well-being and autism and surveys and clinical experience suggest that wellbeing can be achieved by having time in the day when they are not disturbed within their own private sanctuary, being able to excel in what they enjoy doing, and freedom from sensory pain. These are all achievable.

In my extensive clinical experience, I have known autistic children who have what we describe as autism pure, with no signs of a mood, medical or psychological disorder. By their early twenties they have gradually acquired social abilities to make and keep friends and relationships and achieve successful employment and financial independence. The social puzzle is finally solved. They still have the characteristics of autism, but at a sub-clinical level according to the diagnostic criteria. I estimate that this occurs in about ten per cent of patients on my clinic list. I am prepared to remove the diagnosis of autism, but only with the patient’s agreement and for their benefit. Our new conceptualization of autism is that for a few autistic adults there may be a delay in acquiring specific abilities, not an eternal absence.

Finally, over 50 years I have contributed to the growing literature on autism for professionals, parents, and autistic adults. My original book Asperger’s Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals was published in 1998 and has sold over half a million copies and been translated into 30 languages. I continue to write guidebooks on autism and books on therapy for anxiety, depression and emotion expression and regulation. There are now hundreds of books published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers in London on many aspects of autism such as catatonia, having an autistic partner and coping with being in prison and aging and autism.

Recently I have been able to provide professional and parent training through live and recorded webinars. These webinars are available at www.attwoodandgarnettevents.com and are a way of passing on my evolving exploration and understanding of autism.